Michael Eisenberg is a General Partner at Aleph, an equal partnership and early stage venture capital fund with over $500m under management.

Michael was born and raised in Manhattan, in a great Orthodox Jewish household, and attended Jewish day school and high school. His father was a rabbi and lawyer. His mother was an entrepreneur. Today, he has 8 children and 3 grandchildren. He joined us as our guest on Episode 96 of the Agents of Innovation podcast, which can be found on Apple Music, Spotify, Stitcher, Audible, and wherever you listen to podcasts.

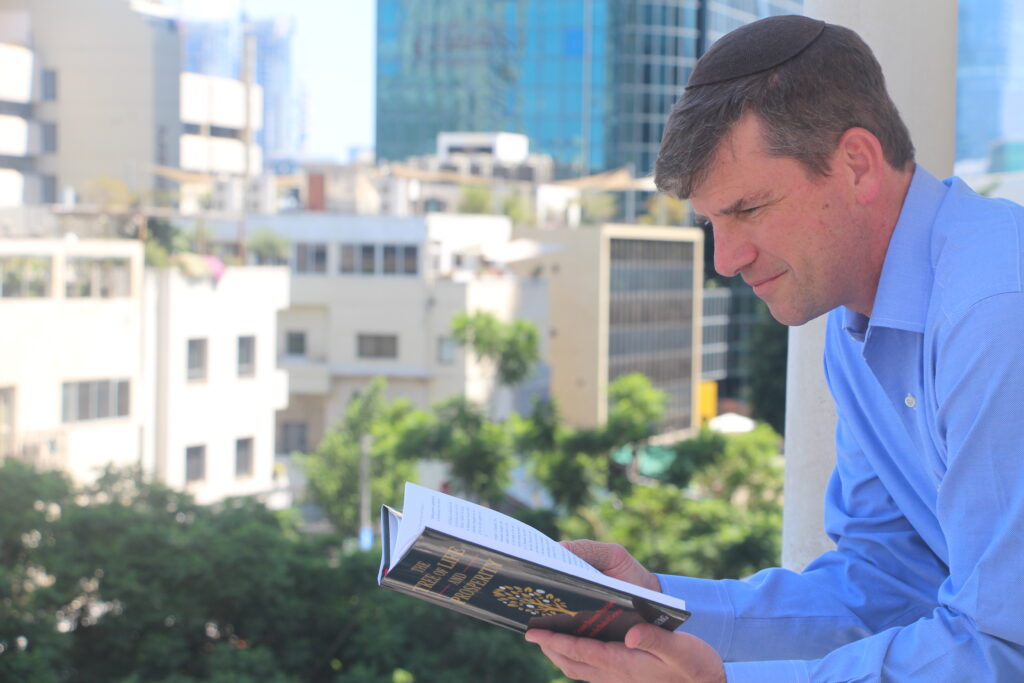

While he has written five books, in 2021, Michael released a new book, The Tree of Life and Prosperity: 21st Century Business Principles from the Book of Genesis. Throughout the book, he creates a framework that uses the words and actions of the Hebrew patriarchs to lay the foundations for a modern growth economy based on timeless business principles and values.

Perhaps Michael learned these principles in his first job, which he started in the eighth grade at a cheese and fish store called Miller’s Cheese. He did everything from slicing cheese and fish and doing deliveries.

“Retail is a great way to meet people,” said Eisenberg — including difficult people in New York City. He did this all the way through high school. He began college in 1988, at Yeshiva University, and took a gap year to go to Israel. While he majored in political science, he also studied the Torah.

“One year turned into two,” said Eisenberg. “That was a transformational experience for me.” He then went back to New York and finished college at Yeshiva University. Within 8 weeks after graduation, he got married, and he and his wife moved to Israel.

During his youth, Michael was always bothered when his mother used to say that “she prayed to have mediocre children.” But later in life, he understood his mother’s prayer, especially her added statement that “the line between amazingly accomplished and intelligent and crazy, on the other hand, is a thin line.”

During the two gap years he was in Israel, an interaction with a rabbi there “changed my views on a lot of things,” admits Eisenberg. The rabbi told him one of the ways he could use his faith was to move to Israel and open up a factory and employ 10,000 people to help them earn an honest and decent living. This was an “economic empowerment argument from a rabbi,” said Eisenberg. “I had never heard anything like that before from a faith figure.”

While he said the pursuit of creating jobs for more people in Israel remains his life goal, the way he has set about achieving that goal has shifted a few times. He began his work life in Israel in political consulting. “But a year plus in political consulting taught me that you don’t create jobs with that.” In his latest book, he takes off on this point further.

“Most politicians focus on present needs. In general, they react. They contend over today’s voters, not over what kind of society their children and grandchildren will live in. I prefer the approach of entrepreneurs who see the world in terms of what could be and tackle a problem that they want to solve. These entrepreneurs think of their product in terms of how much it will help and how many people will buy, use, adopt, and gain benefit from it.”

So he decided on a route of venture capital, where he says the role of a venture capitalist is to “service entrepreneurs.” In the interview on the Agents of Innovation podcast, he added that he thinks “the role of venture capital is to provide the capital for some of the most ambitious projects out there, stuff that normal financial instruments don’t fund. At the same time, it’s to help the entrepreneur build a company, build the management, find the talent, build a network that helps the entrepreneur because we’re in this in an iterative game — meaning we fund a lot of companies — and the entrepreneur has a singular focus.” Quoting one of his business partners, Kevin Harvey, he said the role of the VC is to “lower the mountains and raise the valleys” for the entrepreneur “because this is a helluva roller coaster to build a company.”

In his book, Eisenberg positions many of the Biblical figures we know such as Noah and Joseph as not only people who were great moral leaders (and, at times, moral failures), but also as great innovators, as they lived in pivotal periods of human history.

Eisenberg said we kind of lose sight of these men of the Bible as “innovators” because we treat them as individual protagonists. “Most people know Noah as who was he? He built the ark and got out of the flood,” said Eisenberg. “Noah clearly invented the plow or something like that, that uncorked human prosperity for a meaningful period of time, causing humanity to grow.”

Noah was responding to an ancient version of Thomas Malthus who, in more modern times, believed there would not be enough food if the population kept growing.

“That happens in every generation,” said Eisenberg. Noah didn’t only get past this by inventing the plow, allowing people to grow and cultivate more food, but he also invented fermentation. “We all know that when there are floods, there’s no good drinking water, and wine was the water of the ancients because it was alcoholic and clean.”

“But both of these innovations which could be used for good could also be used for bad,” said Eisenberg. “In the case of the plow, humanity destroyed itself from prosperity. In the case of wine, his son abused him.”

During the time of Noah, people had kids but “begin to become rapacious beasts,” said Eisenberg. “Societal trust becomes eroded as people begin to cheat each other. And so, Noah invents the plow and humanity unleashes itself but begins to destroy itself.”

Through these two innovations, the plow and wine, Noah uncorks both good and bad. Why did these innovations become bad? Eisenberg says it’s “because [Noah] didn’t accompany these innovations with timeless principles and those timeless principles only come into the world with the advent of Abraham, ten generations after Noah. And so, in a world devoid of morals and timeless principles, Noah’s innovations will go bad.”

Eisenberg says this is a lesson for us in modern times, with modern innovations. “If they are not undergirded by timeless principles, they will necessarily go awry.”

In another case, “Joseph innovates long-term storage of preserving wheat, which was, before that, unpreservable,” said Eisenberg. “Through this, he manages to get [Egypt] through the seven-year famine.” Joseph saved the Egyptian people initially, but because he injected so much liquidity into the economy, every shock to the economy shocks the system systemically.

“Therefore the kind of unforeseen unforeseens are more dramatic than ever because the whole system is centralized and thereby very fragile. And so Joseph was unable to foresee a lot of the negative consequences — some of them psychological, some of them population transfer, and some of them economic — because of his policy, and it became hard to restart the economy after the depression, after the famine. When it became hard to restart the economy, they started to look for a scapegoat. That often happens. People who are in trouble after economic depressions look for a scapegoat.”

Eisenberg argues that the failures that stemmed from the centralization of the economy caused the Egyptians to blame the Hebrews and enslave them.

“The thing I’m advocating for,” said Eisenberg, “is the Torah, or the Bible, has timeless principles that have stood the test of time. The Bible has more unique users than Google and Facebook combined. These are the things that have stood the test of time and created successful, cohesive, responsible societies and economies.”

“The responsibility economy is really what the Bible is advocating for,” said Eisenberg. But he says the Bible clearly is not looking to “redistribute the playing field. The Bible does not believe the economy is a zero sum game … it believes the economy can grow through empowerment and what we are looking to do is empower more and more members of society … that’s fundamental to the Biblical outlook.”

“Also fundamental to the Biblical outlook is the importance of being creative and creating, thereby advancing the economy, thereby advancing humanity” said Eisenberg. “The Bible thinks that general human impulses can be used for good and can be used for bad. And so the Hebrew Bible puts limits on general impulses.”

Eisenberg talks about the story of the Garden of Eden, as a place that really embodies what some today might call the Universal Basic Income. Everything is provided and everything grows. Man has everything he needs to live.

“Interestingly, in the Garden of Eden, man makes nothing,” said Eisenberg. “He doesn’t make products and he doesn’t make babies … not only that, they are so bored because they don’t know what to do that his wife never says a word to him nor does he say a word to his wife. She only talks to the serpent. They are terribly bored.”

“The Garden of Eden is more like a failed experiment than it is some sort of idyllic future that we aspire to,” said Eisenbrerg. “It’s a place where man fails and has moral failings and kind of breaks boundaries by eating from the Tree of Good and Bad. Once expelled from the Garden of Eden, man has children, the highest form of creation. Man makes bread.“

Eisenberg points out that while many believe that when the man is expelled from the Garden of Eden that man is cursed, that the Bible actually says “the land is cursed.” And so man must work the land.

“By being forced to work, man becomes creative and this begins to advance humanity. Man left to his own devices on a subsistence income will create exactly nothing.”

“There’s a notion that we work to make money so if we give people money they don’t need to work. No, we work because the human being needs to create,” said Eisenberg. “We need to work to advance the world. And not just that. When we work, we achieve dignity because we created something and made it ours.”

Eisenberg also turns to the role of philanthropy. “The Jewish view of charity is that you enable people to work with dignity,” he said.

“The Bible is primarily worried about prosperity and not poverty, which is the Bible wants people to be prosperous, but is afraid of the impacts of prosperity that people will be haughty, rapacious, not helpful to others, selfish, etc,” said Eisenberg.

“All the patriarchs of the Bible are extraordinarily wealthy people. There’s an expectation there that as the people enter the land of Israel they will become wealthy — and this is an aspiration, by the way — they will become successful and wealthy, etc. We aspire to that, but we don’t aspire to it without the responsibility that comes with it. And this responsibility is not just about kind of managing it paternalistically on behalf of others as Andrew Carnegie suggested in his famous treatise about wealth, but rather to empower other people to become successful as well.”

Eisenberg lifts these ideas from the Book of Leviticus that “it is my civic responsibility, when you become successful or as you are becoming successful, to enable other people to become successful.”

“Freedom is an important part of this because, if you’re not free, you own nothing. That’s an important lesson of the bondage in Egypt. We need freedom. Freedom is the engine of curiosity. Freedom is the engine of aspiration. Freedom is the engine of ownership and ownership gives me the opportunity to be responsible for somebody else.”

Pivoting from the Book of Genesis to modern times, Eisenberg says today is “the absolute golden age of Israel innovation. I’ve been doing this for 25 years and I have never seen anything like what’s going on right now. Entrepreneurs are aspiring to global greatness in ways that wasn’t true before.” He adds that, “right now Israelis are aspiring to build world-scaling companies” and that “the other thing we discovered along the way is that Israel is really about innovation with a soul.”

“The 20th century was about factories,” said Eisenberg. “The 21st century is a digital economy and so it’s about brains … it turns out that brains are connected to bodies and bodies have hearts and souls. And so, if you want to attract the best brains you probably ought to talk to people’s hearts and souls. It’s not just an intellectual challenge, it’s: what do you connect to humanly, what do you aspire to do?”

In his book, Eisenberg says that venture capital is “a business steeped in faith. Faith that the future will be better. Faith in people, entrepreneurs, and changemakers.” In our conversation on the podcast, he added that “I think that people in faith in general think that the future is better.” He added that, “You invest in entrepreneurs because they make the future better. And sometimes it takes a long time and there are ups and downs. It’s a real roller coaster to be an entrepreneur. But if you have a belief and an optimism and a resilience to get through it, that the future is better, there’s no better place to be an entrepreneur and a venture capitalist because you can create the future, and you can create that better future.”

One of the ways investors and entrepreneurs are creating a better future is through what’s called ESG investing – environmental, social and good governance investing. While he believes this renewed focus on ethical investing is good, Eisenberg has a bigger vision for it.

“I much prefer to think of this in terms of longer-term value and more important even than that is that the principles are built into the business themself … it makes the companies themselves much more valuable.” He said, as a venture capitalist, he looks particularly for entrepreneurs who have timeless principles built into the product or brand rather than external to it.

Michael Eisenberg’s biggest advice to anyone, including innovative entrepreneurs, is to have children. “The reason to have children is you learn to love people unconditionally, adapt to the diversity of different people and different kids, and be optimistic about their future and plan for a better future. We need as many people as possible engaged in creating a better future.”

You can listen to the full interview with Michael Eisenberg on Episode 96 of the Agents of Innovation podcast on Apple podcasts, Audible, Spotify, Stitcher, SoundCloud, or wherever you listen to podcasts (and please don’t forget to write a review on any of those platforms!) You can also follow the podcast on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

For those looking to directly connect with and learn from the many guests of the Agents of Innovation podcast, please consider joining the Fearless Journeys community today!