In 2015, Mike Mannina joined Thrive Farmers, an award-winning social impact coffee and tea company, to lead its impact strategy and launch ThriveWorx, a sister non-profit dedicated to disrupting poverty through market-driven collective action. He was our featured guest on Episode 99 of the Agents of Innovation podcast, which is available on all the major podcast platforms including Spotify and Apple podcasts.

Today, the Thrive Farmers and ThriveWorx duo has been dubbed by B Lab “Best for the World,” by bringing customers exceptional coffees, teas and more while helping farmers earn up to 300% higher profits. ThriveWorx then spurs locally-led development by equipping community leaders with a holistic development approach and a network of global resources.

Prior to leading ThriveWorx, Mike served in various roles within the U.S. government in Washington, DC and the Middle East. He served as the U.S. Treasury Attaché to Saudi Arabia, advised economic development efforts in Afghanistan and the Middle East, and worked in the White House. Mike also served as research assistant to Heritage Foundation Founder Ed Feulner and interned for a member of Congress.

Mike was named a Council on Foreign Relations Term Member (2014-2019) and received the University of Georgia’s 40 Under 40 award. He holds business (BBA) and journalism (ABJ) degrees from the University of Georgia and a Master of Arts in Strategic Studies from the U.S. Naval War College.

In his teens, Mike built his work ethic through a variety of jobs: mowing lawns, working at a tennis center, coaching a swim team, and serving fast food at McDonalds and Chick-Fil-A.

“From 9 [years old on] I was always working in some way.” These jobs taught him how to problem solve and deal with customers. “I think all of those experiences set me up when I went to Washington. I was already scrappy. I kind of understood how to navigate a lot of different scenarios. So I look back to those early jobs as both a work ethic of sacrifice and not feeling like I’m too good for any job. I need to serve in some way.”

“I am one, having read a lot of classics, to see that I do think humankind doesn’t really change much through history, and so the earlier you tap into understanding how we as humans interact with each other, the more success in a career you can have since everything revolves around people.”

Mike attended the University of Georgia, and with his self-described “dual-brain” he enrolled in the business school and studied finance. He also enrolled in the journalism school. These served his love for the business side of his brain and the creative side of his brain. However, at the time, the university was not set up for dual enrollment. He was told he had to pick one school or the other.

“You’ve gotta be proactive when you know you really need to do something,” said Mannina. “Nobody is going to make it easy.” He went all the way up to the Vice Chancellor of the school just to get authorization to enroll in both the journalism and business schools. “And I did it. Apparently it paved the way for other students to do as well,” he said.

In college, he was always tempted with the possibility of internships. But he never did that. “I always spent my summers doing things that were just off the beaten path.”

One summer took him to Peru. He received a two-month grant that helped pay for him to be there. He volunteered in the northern part of the country. “It totally wrecked my world of seeing the disparity of these kids that had no parents, who lived way below the poverty line. I just felt like: this is not how we were created. This is not true flourishing. It really broke my heart. It really caused me to question a lot of things,” said Mannina. “And it put me on a deep journey to figure out: what can I do in my life to alleviate some of the suffering. I wasn’t thinking I could solve it all. That’s what really brought me to Washington.” He went there right after graduating from UGA.

“As I went to DC, education to me was much more learning by doing than formal,” said Mannina. He worked at the Heritage Foundation, and specifically for their founder and president, Ed Feulner, who taught him a lot.

After getting rejected over and over again for a job in the Bush White House, he eventually landed a job there in 2006. “I learned from my past interviews, you have to show 100% enthusiasm and I was so hungry to work there that I was basically begging them,” said Mannina.

His first responsibilities in the White House were not glamorous. While he landed a job in the legal counsel’s office, “the first six months I think I made tens to hundreds of thousands of copies of legal documents in response to Congressional inquiries.” After eight or so months in that role, he was given an opportunity to move to the Homeland Security Council.

This taught him something about career journeys for advice he now gives to others: “Finding amazing opportunities that just sort of come and then knowing when to strike and go into them and then be willing to make tons of copies.”

Mike said making those copies is not what he really wanted to do, “but it was for a cause that I believed in and I was like if I’m going to make copies, I’m going to make the best copies out there.” He also problem-solved by finding how to fix the copy machine every time it jammed rather than waiting for someone from the tech department to come do it.

Mike was then promoted into the West Wing, into the Homeland Security advisor’s office and described his role as sort of the “strategy whip” of the organization. They covered counterterrorism to disaster response to nuclear policy and everything in between. Having to deal with a “wide array of information” coming to that office, he described this time as a “fast-paced experience, lots and lots of hours and working around some of the greatest human beings on the planet, some of the most committed, intelligent, and most humble.” For him, this experience “shaped my expectation of what humans could do when we work well together and what people who are really committed to a mission can accomplish. It’s hard to find that.”

It’s also what he tries to build into his organization now, in terms of how he hires, how he builds, and how he finds people who are so committed to the mission.

While working in government, Mike also took advantage of an opportunity to enroll in a master’s degree program at the Naval War College. This was while working on Capitol Hill and also in the White House. During this time, he also met his wife, got married, and started having kids. He has three today.

From there, he was offered an opportunity for a career position in the U.S. Treasury Department, which involved “the nexus of national security and economics.” After a few years, he accepted a role as the U.S. Treasury Attaché to Saudi Arabia. He and his wife and first child moved there and lived there for three years. “I found it a very fascinating and vibrant country,” said Mannina. One thing he learned is that “American business has far more influence than the American government on diplomacy – knowing that Coca-Cola is in far more countries than the U.S. government has a diplomatic presence.”

After his time in Saudi Arabia, Mike and his family returned to the U.S. He could have taken many lucrative jobs including one in New York City. But his dad was going through treatment for leukemia, and he wanted to be near him, so he moved back to the Atlanta suburbs. “It felt very much like it was time to move home,” said Mannina. “It didn’t make sense from a career standpoint at the time, but it was a clear calling that I felt. That put us on a journey to where we’re at today.”

With his years in government and the effectiveness he was bringing to those roles in Washington DC, he said “it didn’t make sense at the time to leave all that.” But in 2014, through a connection, he met with one of the founders of Thrive Farmers and heard his story of “wanting to solve a global crisis in the coffee industry that really leaves millions and millions of farmers in the dust, and finding a way, through the marketplace to rebuild that economic system: how farmers are compensated and how customers engage the producers.”

His experience in Peru during his time in college and “that whole calling towards the poor of the world” came rushing back into his mind. His one-hour intro meeting with a founder from Thrive Farmers turned into a three-hour meeting. “I thought I was just giving him advice and we were just having fun and basically that led to an offer.” Mike laughed because he thought it had nothing to do with what he had been doing in his career.

“I started looking in and realizing this is actually not any different than what I’ve been doing,” said Mannina. “My whole purpose has been to build flourishing societies.”

From a think tank in Washington to the White House; to why he was working in Saudi Arabia, this was the WHY that had always driven him. “And now here was an opportunity sitting before me to do it at a micro level in a way that maybe could rebuild an entire economic system that would lead to flourishing of lots. It kind of started clicking that this was kind of the same thing, just a different iteration – and so I joined.”

Over the past six and half years, he has worked for Thrive Farmers and built ThrivWorx.

While Mike had worked in government his entire career up to this point, he said, “I never felt like a bureaucrat. I always felt like an entrepreneur in every role in government.”

***

And now was his chance to take that entrepreneurial mindset to the coffee industry, In where there are growers and producers. Coffee has to be grown in a very particular environment: the tropics. It also needs a certain elevation, rain pattern, and temperature bands, and soil types.

“It grows in this coffee belt around the world that traditionally has been in the bottom kind of third of prosperous nations. It tends to come out of the least developed countries,” said Mannina. It started in Ethiopia and Yemen and spread to colonized lands, including in the Americas. “It’s an industry that’s built on let’s just say the free or very, very cheap labor and it has evolved to kind of remain the same in that sense.”

Mannina explained how there is a wealthy consumer market that is needing a raw product out of an area that has very cheap labor. “So that’s kind of how the system has been built.”

“The positive side is that humans also have a lot of good in us,” he said. “We’re not all inherently selfish one hundred percent of the time and there’s some real altruism that I think exists. And so fair trade was one of those movements. I kind of like it more in the 1990s of where it was going. It was designed to kind of address a discrepancy in the system: why is it that wealthy consumers can buy this product and the farmers are still living in abject poverty to grow it?”

This led fair traders to try to democratize coffee, create co-ops and collectives, and profit sharing at the farming level. “I think a lot of the intentions of fair trade are quite good and honestly very in line with the team at Thrive and what we feel called to do,” said Mannina. “The difference is in the execution and the evolution of the system. “

But, he said, “fair trade today … it has not really shown a significant difference for the economic disbursements to farmers versus non-fair trade. And in fact, the brand of fair trade is largely a marketing brand. It’s something that consumers recognize so that fair trade can charge a premium to a label for a coffee roaster who can use the fair trade level because the consumer recognizes it.”

Mike also said that “fair trade charges the co-ops – the growers themselves – a fee to be included in this system and then they have to do certain things … some things that are not in their interest, and often things that may not even help the farmer in the end … for a while, the system has not been working well … fair trade also does not guarantee a farmer can sell at a higher price.”

“Thrive was essentially set up to build an entirely different direct system and to remove as many of the costs in the center between the farmer and the consumer.” They remove things like extra marketing fees that aren’t helpful; extra traders who are merely just buying and selling. They give the farmers more equity in the entire process, as it arrives from the raw good to the finished good.

“What farmers end up needing is a partner in the system that says ‘hey, let’s take this product to market together and let’s share in the rewards together.’ That’s what Thrive essentially has done.”

The early farmers that partnered with them gave Thrive coffee on consignment that they then brought to the market. Those farmers get paid a lot more than they would get if they sold their coffee to a trader. Thrive also removes the volatility of pricing that the farmers tend to experience over time, which makes it really hard to plan for investments back into the farm. “We’ve stabilized the price,” said Mannina.

Mannina cited a 2018 study showing coffee-producing countries are capturing about ten percent of the overall value of the coffee that is sold to consumers. This includes the cafe value of coffee, which includes real estate. “All that to say it’s a really tiny percentage” that goes back to the farmer, said Mannina.

He also said that after Thrive’s operations were audited, it has shown that coffee farmers that work with them make about 300% more than they were making prior to the relationship. And when they make those extra profits, it not only helps them but also their community and their country. Mannina says this is far more effective than any government aid they might get.

“Having a marketplace that’s actually taking money from a wealthy economy and fairly paying farmers in the poorer economy creates this huge multiplier effect than anything economic stimulation can do, that farmers can build on it, that communities can build on it, and it actually becomes the foundation for a healthy development strategy there.”

All of the above so far comes from the output of the for-profit coffee company, Thrive Farmers. However, the team there added a nonprofit side to the equation by creating ThriveWorks, where Mannina is the co-founder and CEO.

They changed the structure of the coffee industry with Thrive Farmers. They involved large clients like Chick-Fil-A, which uses the coffee that is sourced from Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Brazil – through Thrive Farmers – for it’s award-winning Cold Brew.

“We need big buyers to understand and buy into a truly fair supply chain, a transparent supply chain; one that really addresses the root cause of the issues.”

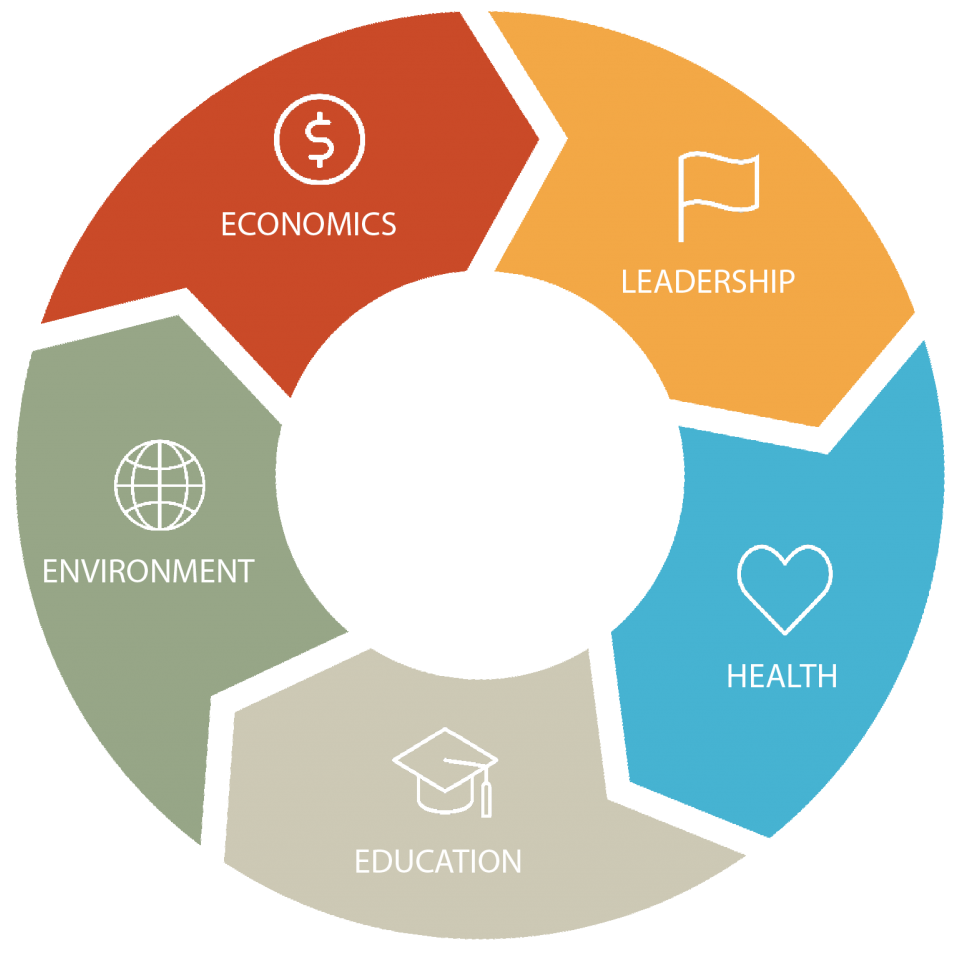

“If you can get the economics moving and expand economic opportunity in a for-profit basis, what if immediately behind that you can have a group that is focused on how do you now mobilize those economics and mobilize community leaders around a development agenda that they create and you empower and equip them to do that with all these different tools?”

Mannina says come up with whatever cultural issue you care about, perhaps the environment or climate change or immigration. The root cause of deforestation, which is unsustainable for their future, in Central America is poor land use, which isn’t solved by government regulation. The root cause of immigration from Central America is a lack of economic opportunity.

“For us, we say let’s address the economic roots of a lot of these other challenges first,” said Mannina. “I would argue in the long run we’ll be far more effective in addressing challenges we weren’t even setting out to address.”

“We are not there specifically to address immigration. We’re there to promote flourishing which at its core will address migration.”

One thing ThriveWorx does is train young people to become baristas or to go into culinary as chefs; or to study at a university and go into computer science or engineering. “We are trying to create alternative tracks [for young people],” said Mannina.

Mannina said the for-profit company, Thrive Farmers, and the nonprofit organization, ThriveWorx, “is not traditional. It’s not like most corporate foundations. Most corporate foundations are set up – you have the company making money – and then the social impact is designed that you donate some of the money to your corporate foundation’s charity and that charity donates and releases those funds to other charities that are doing work with causes that are aligned with the company’s stated desires.”

“We have said: the mission is to build a thriving world and to do that we have got to address the economic disparities of farmers. To do that well, we’ve got to make amazing products that customers want and we’ve got to sell. And then, we’re going to empower local leaders on the community development cycle. It’s a 1-2 punch. I think we would stop short of achieving the mission of a thriving world if we just did one.”

Thrive Farmers produces farmer-direct goods. The products include coffees, teas, and ready-to-drink cold brews and sparkling teas. These can be bought at ThriveFarmers.com. They also partner with companies and distribution companies, but are mostly B2B.

“The only way to solve the big problems we’re trying to solve in the world is scale. And to scale, you need big customers. You need companies that are willing to buy into a transparent supply chain.”

Thrive Farmers also has a physical coffee shop in Atlanta called the Cold Brew Bar. They publish how much they pay the farmers for the price you are paying for that cup of coffee. This is “a subtle way to educate consumers on the economic underpinnings,” said Mannina.” His advice to everyone is “whatever you’re doing, have a good reason why you are doing it and really think how can we make society better in any way.”

Mannina spoke about what the government can do to provide security and rule of law (on the back end), and then what the market can do on the front end, with private philanthropy also serving a role. “ThriveWorx is the epicenter of those three worlds and we’re kind of coordinating it all so that it turns into something beautiful instead of it just being completely random.”

ThriveWorx.org is a bit of a “think tank” that gives people information through a monthly newsletter.

Mannina said his faith is everything. As a lost teenager trying to understand the world he feels like he “had a radical encounter with Jesus and it opened my eyes that I believe we were created by a loving and good God in this perfect order and I believe that we did mess it up and yet there is this pathway back.”

He also said that shaped his Peru experience, “coming face-to-face with poverty” and giving him a “real healthy tension.” He said, “If we only have one life, how are we going to live it? I really do want to honor God in how I live. It is the kind of underpinning motivation in all of Thrive. It’s kind of our why.” He said Thrive chooses “to leave profits on the table and we give them to farmers.” And he added, “I believe it’s the right thing we do.”

“We are inclusive to anyone and everyone. You don’t have to subscribe to the same belief system. We believe you were designed to flourish and our job is to help be on your journey to flourishing.”

Mannina urges aspiring entrepreneurs to be “really spending time to reflect on your why. Until you understand that, ‘Why are you here? Why were you created?’ Until you wrestle with those big questions, there’s a lot of aimlessness.”

He also suggests people to consult what he calls “timeless literature,” things that have “stood the test of time,” such as works by Marcus Aurelius, Plato, Victor Frankel, Augustine, and the holy scriptures. He also suggests building and investing in deep friendships – especially ones that last for a lifetime. “Too few people have built real friendships that are honest,” said Mannina.

And, finally, he suggests that we journal, so we can “get in the habit of putting your thoughts and where you are and what you’re frustrated with and what you’re sad about – put them in writing – over time you’ll have this library of this journey you’ve been on and it will really help you unpack those lessons later.”

“Most new ventures – most new innovative ideas – the world really does reject,” said Mannina. He urged entrepreneurs to have the tenacity to not give up.

“Even for ThriveWorx, we are six years in and we have had a lot of success. I still feel like most people in our closest circles don’t fully see what the founders can see. We can see something the others can’t. Sometimes you just have to stay dogged for years about what you know is right. But you need to make sure you’re right, and you need to constantly be bringing in new input.”

Overall he said we can all “learn how to work and overcome things that you don’t like.” He added, “We are all on our journey. Everyone is going to look different and I praise God for the one He’s had me on.”

You can listen to our conversation with Mike Mannina on Episode 99 of the Agents of Innovation podcast on Apple podcasts, Audible, Spotify, Stitcher, SoundCloud, or wherever you listen to podcasts (and please don’t forget to write a review on any of those platforms!) You can also follow the podcast on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

For those looking to directly connect with and learn from the many guests of the Agents of Innovation podcast, please consider joining the Fearless Journeys community today!